[A] ALTHOUGH PABLO PICASSO WAS born in Spain, lived most of his life in France and never visited the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the United States Department of State maintained a voluminous secret dossier on the titan of 20th-century art. These documents show that high officials spent a good deal of time and effort worrying about what effect Picasso, who joined the French Communist Party in 1944, might have on American opinion and how best to use him for propaganda purposes.

It is a measure of the cold war hysteria of the 1950’s and afterward that Picasso’s very name aroused fear and wonder in Government circles. Recently, Robert B. Davenport, Inspector in Charge of the F.B.I.’s Office of Public Affairs, declined to comment on why files were kept on foreign citizens, then or now, but he noted, “There is no current investigation on Pablo Picasso.” Even though the artist died 17 years ago at the age of 91, the Picasso file continues to be maintained in the F.B.I.’s headquarters in Washington.

American citizens have long had files kept on them because of their political views and affiliations, beginning in earnest in the early 1920’s with J. Edgar Hoover’s rise to power as F.B.I. director. But recently declassified documents reveal that Europeans in various fields of the arts were also tracked closely, without their knowledge, both at home and when they traveled here, or intended to. A few months ago, after a two-and-a-half-year wait, I obtained the Picasso file under the Freedom of Information Act from the F.B.I and the State Department, both of which maintained files on the artist. Originally my interest in the material had related to a book I was writing, “Dangerous Dossiers,” which came out last year. In the book I disclosed that the F.B.I. had files on prominent authors, including the Nobel laureates Thomas Mann, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck and Pearl Buck. In the book I also included the files of four artists: Alexander Calder, Ben Shahn, Georgia O’Keeffe and Henry Moore.

Many of the files of authors and artists showed that they were watched by the F.B.I. because they had sided with the Loyalists against Franco’s Fascists during the Spanish Civil War. Since Picasso had painted “Guernica” as a protest against the deaths in the Basque town caused by Luftwaffe bombings in support of Franco, I wondered if a file was kept on the artist.

I made my first request to the F.B.I. in 1987 and finally received the Picasso file last June. One reason for the delay was that some of the documents had to be cleared by the State Department. I also discovered that the rules governing the Freedom of Information Act had been tightened by executive order during the Reagan Administration. Under the new regulations, F.B.I. documents were reviewed and censored more closely than in the past.

Some pages were withheld altogether and others had entire paragraphs blacked out. Among the reasons for this given to me by the F.B.I. were that the information could “reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy,” or “disclose the identity of a confidential source” or could be “kept secret in the interest of national defense or foreign policy.”

The files showed that Federal agencies kept track of Picasso for some 25 years, monitoring what he wrote, said and signed, his whereabouts and affiliations with other distinguished figures in the arts — including Fernand Leger, the writer Louis Aragon, Le Corbusier and Charles Chaplin. In these files, Picasso is labeled by the F.B.I. as a “Security Matter — C” (for Communist) and as a possible “Subversive” — by its standards a threat to the security and welfare of the United States.

But an analysis of the 187 pages in the Picasso dossier shows no evidence to prove these allegations.

As far as can be discerned from the heavily censored material, the Picasso dossier was begun in 1944. There are references to the artist, dating from his fund-raising activities after the end of the Spanish Civil War on behalf of refugees from Franco’s Spain. For example, his name turns up in the file kept on Dorothy Parker, the American writer, who was chairman of the Joint Ant-Fascit Refugee Committee. Although Picasso was clearly anti-Nazi and anti-Fascist (he refused to return to Spain while Generalissimo Franco ruled his country), he had rejected an opportunity to escape to America during World War II, preferring to continue working in Paris even after the city was occupied by the Germans. During the occupation the artist continued to work industriously. It was forbidden to exhibit his pictures or print his name in the newspapers.

As early as 1945, Hoover personally ordered his special agent in the reopened American Embassy in Paris to keep an eye on Picasso. In a memorandum dated Jan. 16, 1945, one of the key documents in the Picasso dossier, Hoover wrote: “In the event information concerning Picasso comes to your attention, it should be furnished to the Bureau in view of the possibility that he may attempt to come to the United States.”

What initially turned Hoover’s attention to Picasso, according to that document, was a statement written by the artist in 1944, called “Why I Became a Communist.” It reads, in part: “My joining the Communist Party is a logical step in my life, my work and gives them meaning. Through design and color, I have tried to penetrate deeper into a knowledge of the world and of men so that this knowledge might free us. In my own way I have always said what I considered most true, most just and best, and therefore, most beautiful. But during the oppression and the insurrection I felt that that was not enough, that I had to fight not only with painting but with my whole being. . . .”

In 1950 Picasso contemplated a trip to the United States. His file contains a report from The Washington Post, dated March 4 of that year, noting that the State Department had refused to permit a 12-member European “peace delegation,” headed by Picasso, to visit the United States. The Picasso group was formally called the World Congress of Partisans of Peace, and the State Department branded it the “leading Communist-front organization in the world,” adding that the 12 members “are either known Communists or fellow travelers and are therefore subject to exclusion.”

The Picasso file also contains a communication, dated Feb. 23, 1950, and stamped “confidential,” sent from Ambassador David K. Bruce in Paris to Secretary of State Dean Acheson, weighing what might happen if Picasso were denied a visa to visit the United States. Written in diplomatic shorthand, the message reads: “In view his worldwide reputation, refusal of visa to Picasso would certainly cause unfavorable comment here, particularly in intellectual and ‘liberal’ circles. It would also tend to suggest that we have something to fear from Communist ‘peace’ propaganda. However, if decision is negative, we believe that Departmental spokesman and V.O.A. [ Voice of America ] should point out that proposed visit is a brazen propaganda stunt for purely political motives which have no connection with professional activities of applicants.

“In either event, we would urge that decision be made as rapidly as possible, since the longer it is postponed, the easier it will be for the Communist Party to exploit its nuisance value, which of course is their essential objective.”

Picasso’s file was prepared at the “Seat of Government” — Hoover’s favorite phrase for his headquarters in Washington. Like similar F.B.I. records that repeat raw data, the file contains misspellings and disjointed information; much of the material merely repeats newspaper reports. Picasso’s occupation is listed as “sculptor and painter,” and he is identified by various names: Pablo Picaso, Pable Picasso, Pablo Ruiz Picasso and One Picasso.

The biographical data in the file includes observations about his personal life: “Lived quietly with a woman many years his junior, who was also an artist and Communist, by whom he had two children (names not given).” The reference is to Francoise Gilot, an artist in her own right.

Other documents stressed the artist’s international connections. An F.B.I. memorandum in 1950 cited hearings before a Senate Immigration and Naturalization subcommittee that linked Picasso and Charlie Chaplin. “In reviewing Chaplin’s case,” the memorandum said, “it was brought out that Chaplin had sent a cable to Pablo Picasso, an admitted French CP member, urging him to stage demonstrations against the U.S. in France.” A later memorandum from the Los Angeles office of the F.B.I. questioned the truth of this statement. A third memorandum stated that at the national convention of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, “greetings were read from Pablo Picasso.”

And a 1949 memo from Havana about the Communist Party in Cuba read: “As is known, the Communists have adopted as an emblem of their international campaign a white pigeon painted by the Spanish painter, Pablo Picasso. The bird painted by Picasso belongs to a breed known as a Russian Trumpeter.” The pigeon was obviously a fellow traveler.

An almost totally censored page in Picasso’s file, originating in the F.B.I.’s New York office and dated June 16, 1950, makes the most serious accusation against the artist: “Espionage — R” (for Russia). The file contains no additional documents that would justify placing him in this category.

In 1957, an F.B.I. memorandum labeled “Cultural Activities” and stamped “Secret” was prepared by Special Agent (name blacked out). It commented on a Picasso show at the Museum of Modern Art as it was reported in the Communist newspaper The Daily Worker. The memorandum quoted Alfred H. Barr Jr., director of the museum, as saying, “We do not want to put Picasso in an embarrassing position by inviting him, only to have his entry questioned by our Government.”

While the Picasso file grew smaller in the mid-1960’s, his name continued to appear in F.B.I. references up through 1971, when he was nearly 90 years old.

To find out a little more about Picasso’s political activity, I spoke to Dominique Desanti, a friend of the artist. Madame Desanti and her husband, Jean-Toussaint Desanti, were active in the French Resistance during the Occupation. She said that both she and her husband joined in the armed struggle on the side of the Communists. In 1956, they left the party after the Soviet invasion of Hungary. In New York recently, where she was teaching at New York University, Mrs. Desanti recalled Picasso’s attitude toward the Communist Party in France.

“Picasso, you know, came out of the Spanish anarchist tradition,” she said. “He was a Communist but not a party-line Communist. He never attended his cell meetings in Vallauris, the little town where he lived — if there was a meeting, they came to him . The mayor of Vallauris was a Communist. Picasso gave the party some money, but not much, you know? He was really not a political person but he was interested in society. Coming into the Communist Party was a natural thing at that time for French artists and intellectuals, like Aragon, Leger and Picasso.

“He once told me, ‘If I wouldn’t be a Communist, I’d be the worst kind of bourgeois.’ Had he known the F.B.I. was watching him, he probably would have laughed his head off. He might have put on a mask maker’s red nose and made jokes about it. No doubt he would think such an absurd thing was surrealistic.”

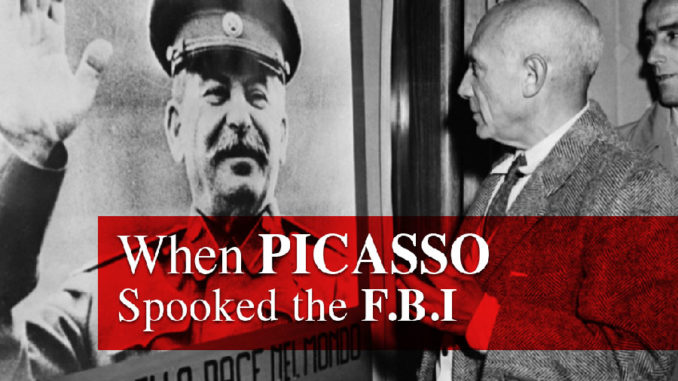

Photo: One of 187 page4s in the Pacasso dossier provided by the F.B.I.– some pages withheld and others reviewed and censored more closely than in the past (pg. 1); Pablo Picasso, far right, at a political meeting in Paris in 1950. The speaker is the French poet Paul Eluard; seated are, from left, the writer Louis Aragon, his wife, Elsa Triolet, and an unidentified woman–“Security Matter-C” (for Communist) (The New York Times ) (pg. 39).

Source: The New York time

By HERBERT MITGANG

Published: November 11, 1990

Leave a Reply